Remembering Philip Ochieng

I've put it off long enough, but now that I'm back to writing regularly, I can feel the weight of it.

My biological father, Phillip Ochieng, passed away back on April 27th at 83. For those who know my history, you can imagine the difficulty I'm having with it. It's not the usual difficulty -- grief. It's difficult to grieve for someone who was never a real part of your life.

Though I know that my Kenyan siblings, nieces and nephews and many others miss him, I think they know this to be true of me. And though it's probably painful for them to hear it, it had to be said.

After a lifetime of being different from other black Americans, I'd like to try to make this elegy not about me, though it's almost inescapable.

My father came to America in 1959 via the Mboya Airlift.

When the students of the Mboya Airlift were hand-picked to come to America, it was for a specific purpose: to educate demonstrably gifted Kenyan and Tanzanian students in the Western tradition and to send them home to be the leaders and information venders of their countries in preparation for independence from the European colonial powers. One of these students was my biological father, journalist Philip Ochieng.

That was in the late fifties to early sixties and most of the students did return home. The Airlift was a privately funded endeavor by the likes of the Ford Foundation, the Kennedy Foundation, Jackie Robinson, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Harry Belafonte. I’m sure that there have been other experiments like it.

My father was famous, though I didn’t know it until I was 35, nearly at the beginning of the Internet Age, when I had the tools to search for him. It was then that I discovered that he was one of most celebrated writers in Kenya, possibly in all of Africa. I had no memory of him because he and my mom divorced when I was a baby, he returned to his native country, and there had been no contact since then. That story might sound familiar.

If I listed all the things that happened since then and now that I am 60, this post would be much longer than it’s already going to be.

In 2016, courtesy of a friend and fan of my blog, I got to make my first trip to Kenya, met my father, my Kenyan siblings and a goodly portion of the rest of my family in the country. It was a joyous, blessed occasion and I hope to make the trip again, even though my father is gone.

His second wife, Jeniffer Dawa, preceded him into the next world not long after my visit. My brother Charles says that Father seemed to lose his spark of life after she was gone.

His funeral was public and online. Many tributes were paid by Kenyan dignitaries and other notables-- and by the many persons that my father helped in their writing careers.

It was a sight to see.

His body was interred at the family compound near Manyatta, Kenya.

Father had two weekly columns; he was very prolific for a long time up until 2020.

One column was on Kenya politics and the other was a treatise — often an erudite rant — on English grammar. It wasn't so much that regular, everyday Kenyans were using bad grammar, it was that Kenyan journalists were using it. I enjoyed that column very much and saw so much of myself every time I read it.

I've always known what my calling was. Remember those times in school when you were about 10 or 11 and the teacher asked everyone what they wanted to be when they grew up? My fellow students offered the standards: doctor, nurse, policeman, fireman, or some other admirable profession.

I didn't want to be any of those. When the teacher got around to me, my answer was almost reflexive: writer. I hadn't even given it any thought.

By the time I discovered that my father was a celebrated writer, I was writing for myself, mostly just to get things off my chest. Then when blogging came along, I began writing for the public and was getting good responses.

It's amazing how alike two people can be when one is descended from the other but there has been no contact between them.

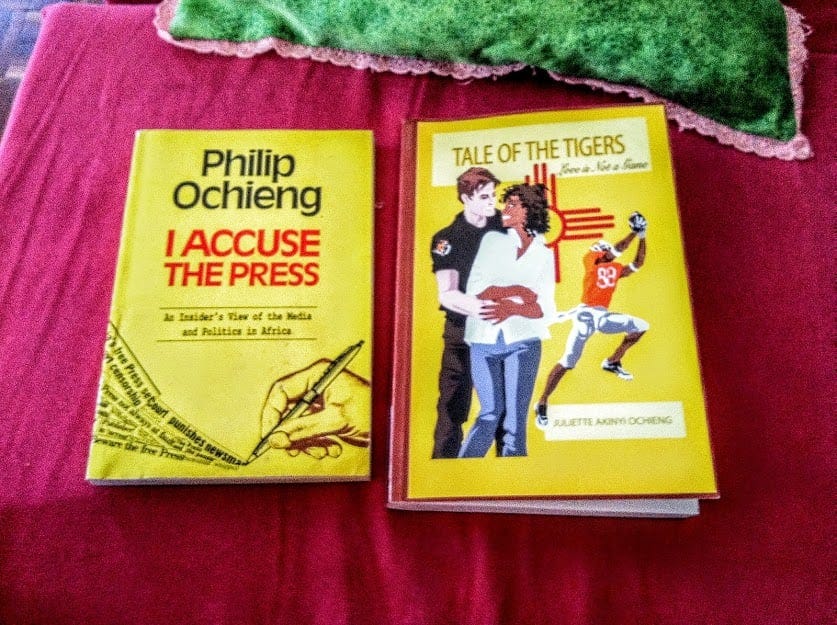

We've both written books. His are: I accuse the press: An insider's view of the media and politics in Africa and The Kenyatta Succession. Additionally, he was the uncredited editor of Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa.

I have only one so far, but here it is next to one of his.

The color scheme is purely “coincidental.” He was impressed that I dabbled in fiction.

His biography, The 5th Columnist, was penned by Liz Gitonga-Wanjohi and published by Longhorn Publishers in 2015.

Here’s a good summary of his life – despite the sensational headline and aside from the fact that there are some grammar errors in it. My mother and I are mentioned.

Wherever he went, Father seemed to have a penchant for pissing off the powers that be.

It is as good a legacy as any.

As I do for all my family members, I prayed for my father – that he would come to know Christ in this life and follow Him. Father was a public atheist, denouncing the existence of God at least once a year in his political column. But Charles says that, in his last days, Father asked the clergyman in attendance to pray for him. So, I’ll have to be content with that.

God saw fit to give me more than one father (three) and more than one mother (two), and I am grateful for all of them. But I know for a fact that many of the gifts I have I came by honestly.

I hope to see you again, Father.

Great column! :)

Master piece writing on dad. You have surely captured him. You surely take after him. May his writing live in you